Moral Brakes

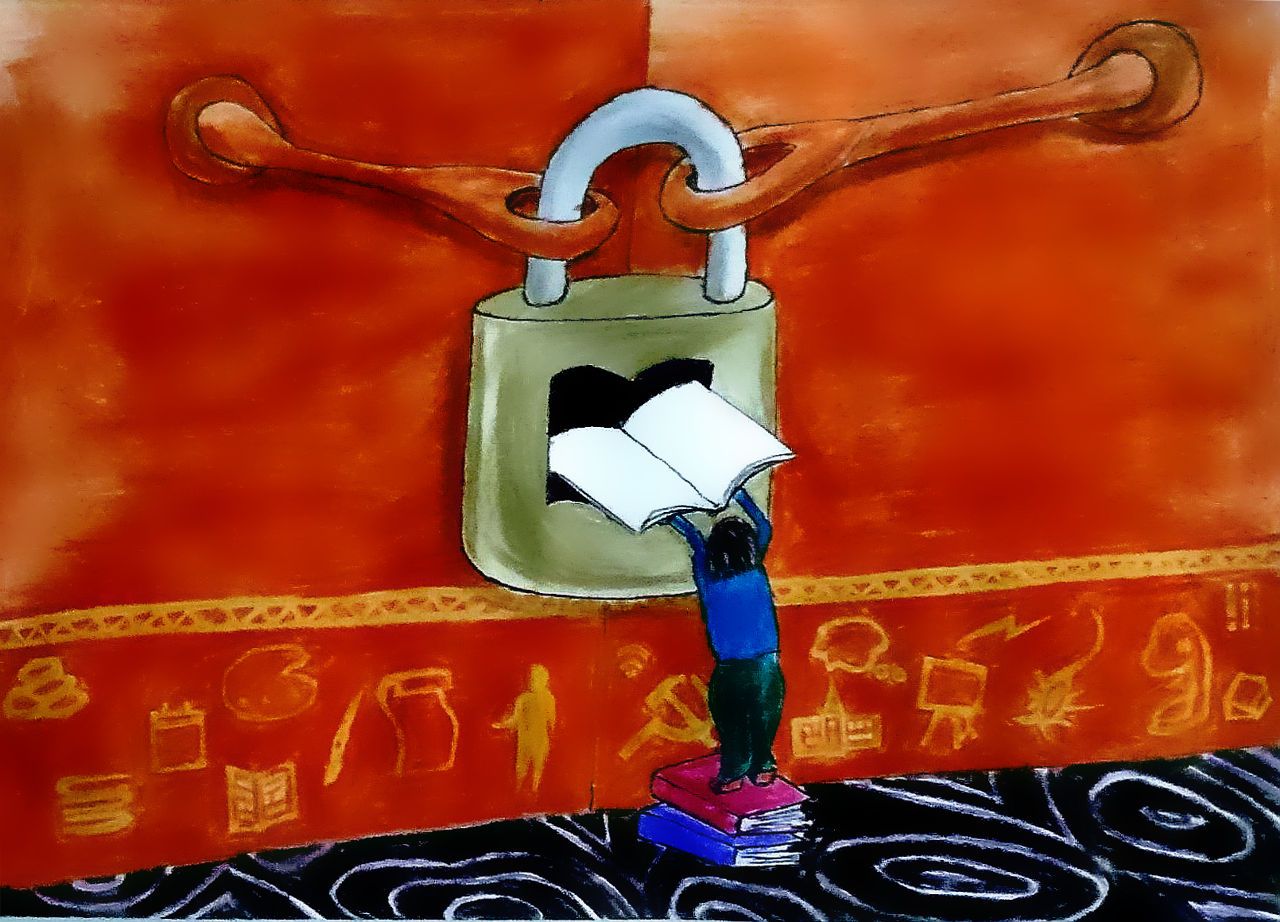

Our incomplete education could end the world. Can the humanities save us from ourselves?

Our incomplete education could end the world. Can the humanities save us from ourselves?

The Humanities. Or, if you’re a science major, the Humanities, followed by an eye roll. We’ve all seen it.

Do people really care about the humanities? Even a cursory glance at education systems around the world reveals: not really. People are more interested in technology, in engineering, in facts and results. The focus is on finding new ways to use the world; we don’t care why or what makes us use it.

But we should. Our future depends on it.

According to biologist, naturalist, and award-winning nonfiction author Edward O. Wilson, the humanities might be the only thing that can save us from ourselves in this period of history where we possess the power to annihilate everything in existence.

“The humanities, of which the study of religion is an integral part, differ fundamentally from science in mode of thought,” Wilson writes. “The humanities alone create social value. Their languages, buoyed by the creative arts, evoke feelings and actions instinctively felt to be correct and true. When knowledge is deep enough and all set in place, the humanities become the preeminent source of moral judgment.”

Wilson goes on to point out that although some things seem inherently good or evil, we must not forget that every thought and action must be placed in a context, both scientific and humanistic, before it can be judged morally good.

The nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki could be deemed morally justified because, even though they killed millions of people, they prevented the deaths of millions more American and Japanese lives which would otherwise have been lost from ongoing fighting. On the other hand, this attack led to the Cold War which produced ongoing moral dilemmas of its own.

So where, Wilson asks, does the solution to our moral conundrum lie? How can we find it?

“Science owns the warrant to explore everything deemed factual and possible,” he says, “but the humanities, borne aloft by both fact and fantasy, have the power of everything not only possible but also conceivable.”

This may sound like a fluffy fringe idea. It’s not.

Thomas Jefferson believed education should provide the means of achieving a citizen’s own livelihood as well as improving his morals and faculties.

It was crucial, Jefferson said, for a person

“to understand his duties to his neighbours and country, and to discharge with competence the functions confided to him by either; to know his rights . . . And, in general, to observe with intelligence and faithfulness all the social relations under which he shall be placed.”

In other, less archaic-sounding words, Thomas Jefferson supported an education system that produced well-rounded, informed individuals who could make course corrections when an idiot gained power and steered society toward rocky shoals.

So why don’t humanities get the attention they deserve?

Every thought and action must be placed in a context, both scientific and humanistic, before it can be judged morally good. — Edward O. Wilson.

A study by the National Endowment for the Humanities found that the period of 1982–2008 saw only 20–25% of Americans visiting an art gallery or art museum at least once a year. Honestly, this much higher than I expected and while I’m pleasantly surprised, these are still low numbers.

The problem? Poverty, Wilson says, and a lack of respect.

Artists are poised with paintbrushes ready, but the modern humanities rarely receive enough funds to finish the projects their artists and scholars aspire to create.

During the Renaissance period, artists enjoyed long-term sponsors, such as Michelangelo’s patron Pope Julius II, but now, monasteries and other religious organizations no longer serve as creative sanctuaries. And in academia, STEM — Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics — and college prep for STEM majors, is valued above all else, even the physical fitness of students, which become a neglected afterthought leading to an obesity epidemic in first-world countries like the United States.

So what’s the big deal? Research and development in STEM benefits the nation, right? We might be putting all our eggs in one basket, but if it’s the basket that’ll lead us into the future, who cares if we neglect the arts and humanities?

We do. Even if we don’t realise it.

STEM is critical to the progress of a nation. There’s no arguing that. In a world where measles has roared back to a top contender for deadly diseases, we can’t ignore science education. But humanities are equally important. Philosophy, jurisprudence, literature, history, sociology — they preserve our values.

They turn us into patriots for moral values, not parrots for demagogues promising empty platitudes. How much better might we make political decisions if we knew how to spot logical fallacies and manipulation in candidates’ speeches?

Philosophy teaches us how to reason, and history warns us the ghosts of our past are not as dead as we’d like to believe — Nazism didn’t die with Hitler, it’s as alive today as anyone who espouses it.

The boon of the humanities goes beyond this. Let’s not forget the wealth of knowledge we mine from psychology. How much better would we make decisions in everyday life and for the good of our society if everyone was aware of the cognitive biases influencing their decisions?

“Science (with technology) tells us whatever is needed in order to go wherever we choose,” Wilson writes, “and the humanities tell us where to do with whatever is produced by science.”

It’s hard to derive a moral code of living or a higher meaning from what STEM alone describes. It’s one thing to say, “All human beings are composed of atoms,” and another to say, “These atoms arranged into the form of people and animals have inherent value and should be treated with respect and dignity.”

A mind all logic is like a knife all blade. It makes the hand bleed that uses it.

—Rabindranath Tagore

STEM isn’t qualified to make moral codes or higher meanings. But the humanities can, and do.

Wilson writes that “the human enterprise has been to dominate Earth and everything on it, while remaining constrained by a swarm of competing nations, organized religions, and other selfish collectivities, most of whom are blind to the common good of the species and planet.”

He continues to say that because the humanities focus on aesthetics and values, they have the power to swerve the moral trajectory into a new mode of reasoning, one that embraces scientific and technological knowledge.

To do this, they’ll have to blend with science, not replace it.

You can’t understand how human societies work, or what’s good for them, without objective scientific research.

For example, you won’t understand why people behave the way they do in groups without understanding that we haven’t evolved much from our hunter-gatherer ancestors. We’re still working with the same neural hardware. That STEM fact influences the humanities.

“Like the sunlight and firelight that guided our birth,” Wilson says, “we need a unified humanities and science to construct a full and honest picture of what we truly are and what we can become.”

These humanities include paleontology, anthropology, psychology, evolutionary biology, and neurobiology. Of these, evolution is paramount.

Let’s not forget, Wilson says, nothing in the science or the humanities makes sense except in the light of evolution.

If you take a look at those five humanities, you’ll notice a common thread. They all directly teach us about ourselves, as opposed to more abstract quantum mechanical theory, which is fascinating and relevant in its own right but can’t be applied to improve our daily lives.

Learning about ourselves is nothing to scoff at. Cultures throughout history and from all around the world teach us that the most powerful tool in our arsenal is the ability to know and understand ourselves. Why do we think the way we do? Why do certain words, ideas, and concepts have more sway over our behaviour than other words, ideas, and concepts?

Knowledge is power, especially knowing yourself, and self-mastery is the first step to mastering anything outside yourself. This is where the humanities come in. This is what we lack today.

We have the ability to obliterate all life on earth, but the people elected to office to control this power are unpredictable at best. At worst, they’re predictably selfish and destructive. And yet, to a large extent, we chose them. Or allowed them to be chosen. Why? Don’t we know what’s good for us?

No. Not without investing in the humanities. We only know what is — what is available in the world for us to take, manipulate, and use up — but not whether we should partake, or if it will make life better.

Again, I’m not saying STEM isn’t important, but where STEM alone can teach us faster ways to extract oil and cut down trees, the humanities can tell us that it’s a terrible idea and we should focus on cleaner methods.

When Thomas Jefferson helped create Western democracy, he foresaw the power and influence it would wield, and he recognized the importance of buttressing our progress with moral guidance and competence, ideals which have fallen by the wayside in modern society.

Edward O. Wilson’s insistence on expanding the humanities may seem like a fringe idea on the surface. But if we want to raise a generation of well-rounded, powerful and moral people, our best bet is to integrate the humanities into education as early as possible, rather than relegate it to “someday, maybe tomorrow” and complain when the train of progress runs off the rails with no moral brakes.