Bridging the Gaps

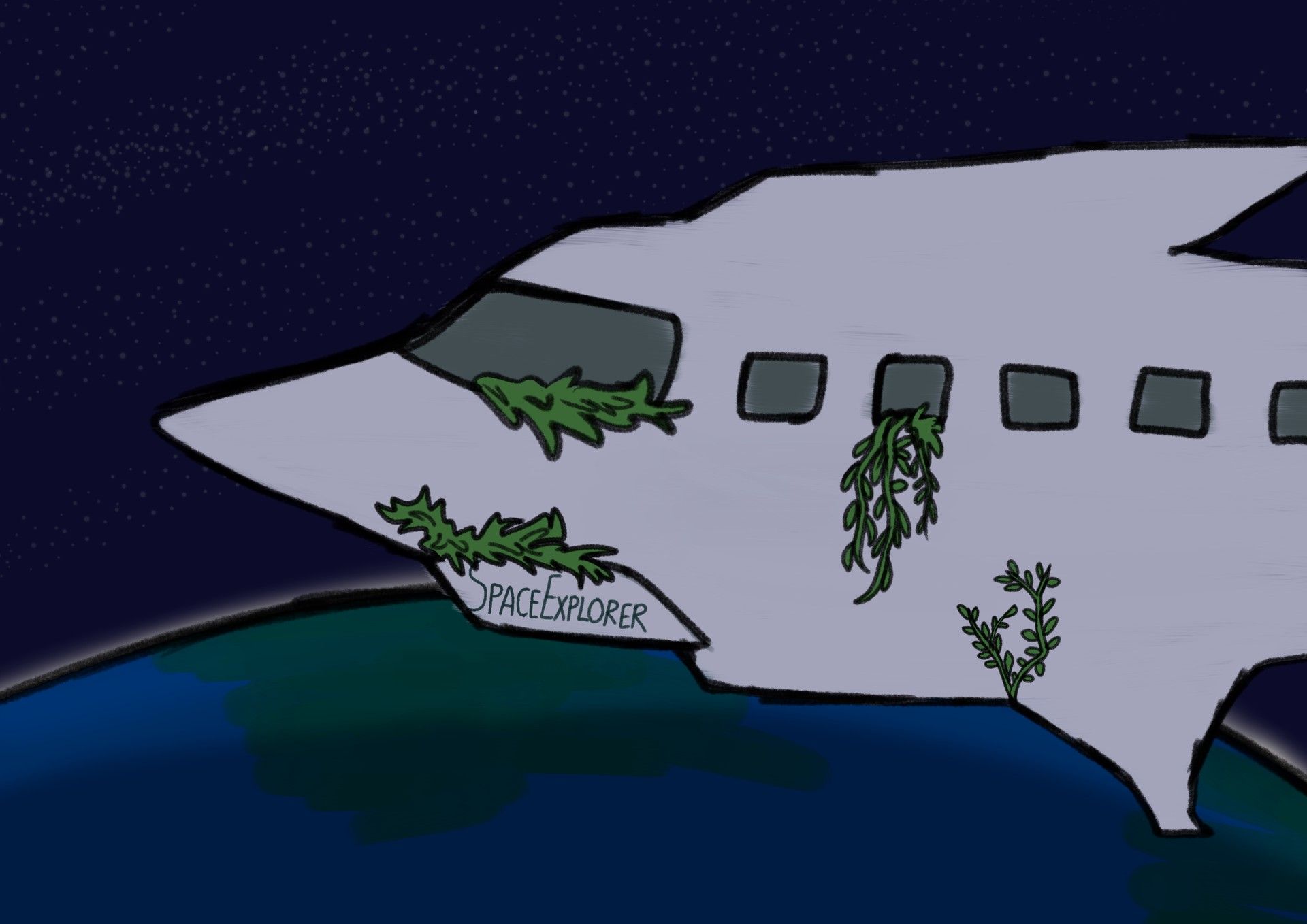

The new space race is on — but will it reduce the space between the rich and the poor?

The new space race is on — but will it reduce the space between the rich and the poor?

Imagine, a family where everyone’s interacting together all the time. A family that shares space constantly, and I don’t just mean emotionally, but physically too. Arguments are flaring frequently and emotions are running high. No one can agree with each other, and every small thing is annoying someone in the house. Mum and Dad are bickering, the children are shouting.

Everyone is driving each other up the walls–literally.

Sound familiar? Well, we have all experienced periods and shades of this through the pandemic. None of us is exempt from this. After all, it’s only when the whole family’s cooped up at home that you realise how small the house actually is, and how little space there is to navigate.

Astronauts who go to space face similar issues: they too have to be together in a small space for a long time, and there is definitely no option to leave. They too have work pressure, magnified because it’s a mission that a crazy amount of money has been spent on, and dependent on successfully being completed.

Nonetheless, this is not what we mean when we use the term ‘Space Race’.

Be it the square footage between the walls we occupy, the blank void between two written words, or the gap between two people as they diligently adhere to social distancing norms–now so much a part of our lives–space is something we all encounter.

When we talk of the Space Race, which garnered so much attention in the late sixties and early seventies, we were not actually too concerned with space at all. What mattered in that competition was who would be the first nation to bridge the gap between Earth and the moon.

Space was merely the void that existed between here and there, an emptiness that needed to be crossed as quickly as possible.

Recently we have seen new races in which the word space is used, but which also actually have little to do with space itself. In one of them, three of the world’s richest men have engaged in a competition to be the first to conquer that world outside of Earth’s gravitational pull. Some will inevitably see this as a wonderful start to another era of subjugating new frontiers. Others seem to see it more like an intense ego-filled competition between billionaires.

In some sense, it’s not much different from when ancient pharaohs were expected to become gods in the afterlife and were thus buried in monumental tombs, where space meant power. The larger the tomb, the greater the space, and therefore the more powerful, and rich.

In more recent past generations, when someone really rich wanted to carve their name on the annals of history, they built a really big fleet of ships and dispatched it across a space of the uncharted ocean. Any landmasses they encountered, it was declared to be a new part of their nation, after having done a fairly lucrative deal with whoever happened to be the reigning monarch at the time. Inevitably, these entrepreneurs acquired huge fortunes, though seldom endearing themselves to the indigenous populations in the process.

Deprived of new worlds to pin their flags to, our modern-day swashbucklers are obliged to look further afield for ways to immortalise their names and burnish their egos.

Space tourism gives individuals–tourists–the opportunity to become astronauts and experience space travel for recreational, leisure, or business purposes. As it’s extremely expensive, very few people can and want to pay for such an experience.

Earlier it was a much more serious matter that was given a certain amount of respect and solemnity. It was an opportunity rarely provided, and those who did get such a chance understood it as the once in a lifetime opportunity. Now, individuals like Jeff Bezos and his friends, degrade such experiences by shouting and laughing all the way up — while the video is beamed to Earth for prime-time TV.

The modern-day space race is by no means limited to grossly rich billionaires. Nation-states continue to gaze upwards. This tendency is especially obvious during times of political unrest or financial instability. After all, encouraging the electorate to dream of life on Mars is one way to take the focus off of more pressing problems closer to home.

In the city of Chidambaram, Tamil Nadu, there stands a magnificent Nataraja temple dedicated to Lord Shiva. Like other large temples, it features ornate towers, courtyards and shrines — all of which are essentially props for the sanctum sanctorum: a tiny room where the real deity resides. And now comes the unusual part. Inside this sanctum, instead of the usual Shivalinga, the symbol of Lord Shiva, there is just…empty space.

This space represents the “formless” aspect of Lord Shiva, and is known as the chit sabha or “consciousness gathering”. It is also known as the “sky of consciousness” or chit ambalam.

Chidambaram isn’t the only place where space is worshipped: in fact, Buddhism and Taoism both give importance to emptiness, and in very different ways at that. And in today’s world, where wealth and power are given more importance than spirituality, we associate large spaces with power — just like the pharaoh’s tomb.

Ironically, a lot of the world’s problems can be described as problems of space. The world’s human population has grown to an unprecedented level, and we’re starting to feel the crunch. That’s one reason the rich and powerful want to go to space: to get away from all the crowding masses down below. Of late, countries have been talking about “the migrant problem”: too many outsiders are coming in and taking up their space. But if you look at it the other way, why did those people emigrate in the first place? It’s because there wasn’t enough space for them in their own countries.

But is our planet really so full up? Perhaps we have the space, but just aren’t using it efficiently enough.

Around the world, humans generate more than enough food to feed the entire population — and yet, hundreds of millions of people go hungry. The reasons can immediately be ascertained if you think about the pandemic: when lockdown affected supply chains, chances are, you were at some point hungry or running short of food as well. A more general problem is that, while we have the means to make enough food, we don’t have systems in place to distribute it properly.

It is precisely this kind of problem where a few funds could go a long way. Thus, here’s another kind of space that I would prefer our leaders and billionaires to target their attention towards. Instead of space exploration, what if those trillions of dollars had been directed towards health care, education and environmental reparation?

Instead of focusing on the gap between here and Mars, how about trying to bridge the gap between the rich and the poor?

With tight deadlines, where even minor delays can be costly, astronauts had better be as healthy as possible. It was to this end that NASA developed the implantable insulin pump, to monitor astronauts’ glucose levels and inject insulin when necessary. This technology was later adapted for use on Earth.

One can find similar stories for memory foam, invisible braces for teeth, artificial limbs, and the all-knowing GPS. Technology that was originally designed for space exploration, but ended up being used on Earth — and sometimes became such common features of our everyday experience that we couldn’t imagine life without them!

Even if you don’t travel to space, it seems, you can still benefit from space travel. Or so the argument goes.

In reality, most of these secondary benefits are minor compared to the vast sums spent on space exploration. Even taking crew members on these missions of spaceflight uses up much more money and energy. Steven Weinberg, a physicist, explains that every single goal that crewed spaceflight are said to achieve, can be performed more cheaply and efficiently by uncrewed flights. Once humans are part of the mission, their safety becomes of the greatest importance so we need to spend loads more to keep them safe. It has been shown that it would be cheaper, and we could gain more extensive scientific knowledge if we use robots.

Oh, and those implantable insulin pumps? They never really got off the ground and were eventually discontinued.

When we stack block upon block in a game of Jenga, eventually we must start removing pieces from lower down the tower in order to build taller. With each piece we remove, the tower becomes slightly higher, but the gaps lower down start to make the tower unstable. Right now, tower Earth is wobbling badly.

An average long-haul flight produces 2 to 3 tons of carbon dioxide per passenger. A single rocket launch can produce three hundred times as much as that. There aren’t as many rockets being launched as there are aeroplanes, it is true, but rocket emissions go right into the atmosphere and stay there for at least a couple of years.

Should we abandon the space race altogether? Maybe not. Maybe what we should be focusing on, is to plug the gaps here on Earth before shooting for the stars. Space is just another gap to conquer, and at the moment we have enough of those here on our own planet to deal with.

Space tourism and the search for precious metals on Mars may offer the lure of greater wealth to those who are already excessively rich, but personally, I would rather have a healthy planet with enough space for all of us.