Aurora Borealis

The princess and the force of nature — and what they have in common.

The princess and the force of nature — and what they have in common

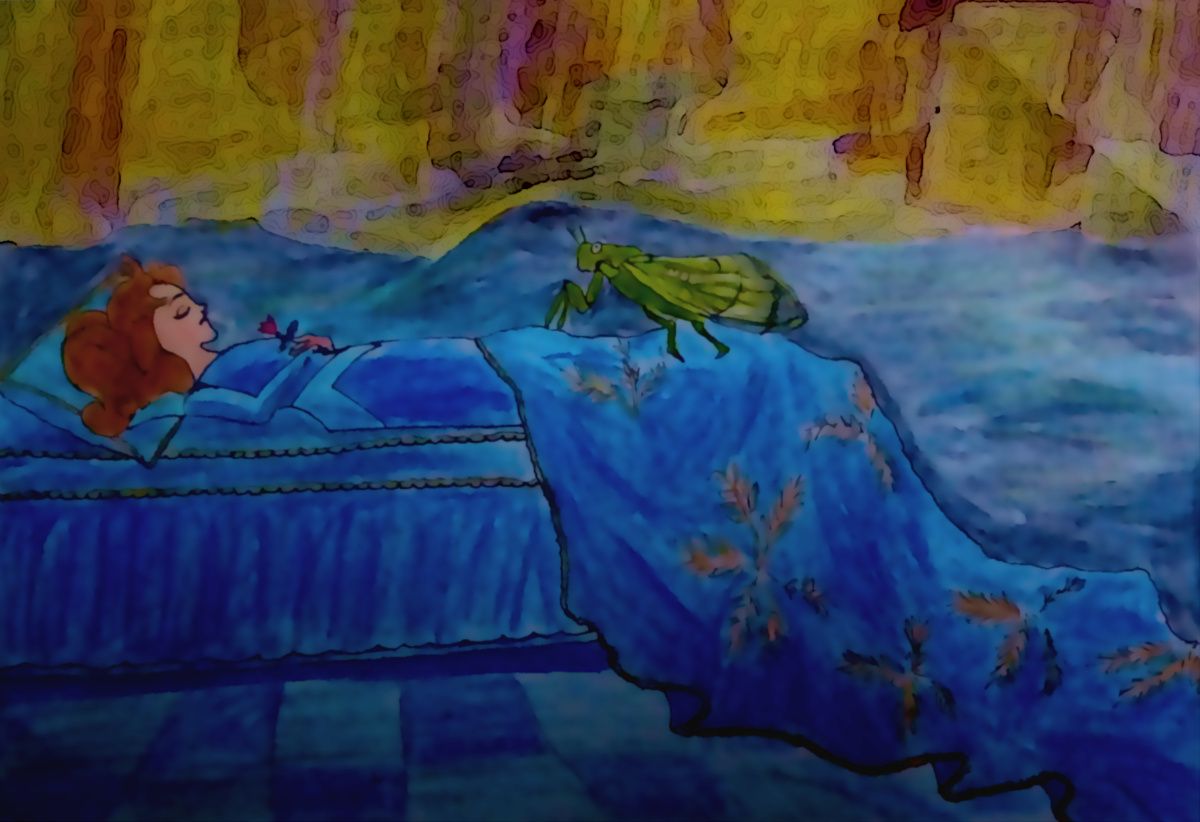

Take a trip down memory lane, to the stories you were told as a child. There’s one, in particular, that’s always stuck with me. It’s the story of a beautiful princess cursed to die if she pricks her finger on a spindle.

Horrified, her parents — the King and Queen — send their little daughter away to be raised in a cottage deep inside the woods, and then proceed to destroy every spinning wheel in the country. As these stories often go, the prophecy is fulfilled regardless: the princess accidentally happens upon a spindle one day…and pricks her finger on it.

Luckily, a kindly fairy has reduced the sentence, so instead of dying the princess falls asleep, but into a sleep so deep that it needs a true love’s kiss to wake her up.

If you’ve watched the Disney version of this story, then you may even remember the princess’s name: Aurora. In this telling, her name is all but incidental to the narrative, but it’s a name with a rich story of its own.

Imagine, for a minute, the entire arch of the night sky flooded with colour: cascades of yellow-green, and a crimson blush from an obscure point high overhead. The lights fall in wide beams: moving and changing; suddenly intense in one place, then another.

This is the sight of the aurora borealis — and it completely draws your breath away.

As author Adi Alsaid rather fittingly put it, “[An Aurora ] doesn’t feel like some accident of nature but rather something that was purposefully unleashed on the world”. They give me the sense of peering deep into the heart of a flower; a flower of great light whose petals undulate in a breeze that can’t be felt: a breath from beyond this planet.

The Northern lights are also considered a symbol of compassion.

An Obijiwa legend goes that during the great flood, a race of people we know today as the mongols were spared for being god-fearing people. But the flood had tilted the Earth, and the fearful survivors no longer had any sun. In his compassion, the Great Spirit led them to a warmer, more fertile place, where the Northern cap of the planet was covered with crystals of ice that could capture and reflect the rays of the hidden sun, splitting them into disparate colors.

The princess Aurora was also given gifts at her coming-of-age ceremony — beauty and a singing voice. It is this beauty, archaic though the idea may be, that helps her later as she is saved by the prince. It is because he is drawn to her beauty that she is saved.

Evil is vanquished; love conquers.

Clearly, the aurora borealis has fascinated people the world over. Our earliest written record of an auroral sighting was penned in 2600 BCE China, describing ‘strong lighting moving around [a star]’ and how the light ‘illuminated the whole area.’

Of course, ever since the first sighting, people have been coming up with various explanations for why auroras happen. In the 1500s, a common idea seems to have been that they stem from candles burning in the sky. A hundred years later, Galileo believed them to be a result of sunlight reflecting from the atmosphere.

Finally, in 1790, Henry Cavendish decided to make some quantitative observations. To determine how far they really were, he used a method called triangulation: look at an object from two different points, and see how much your viewing angle changes. With that, Cavendish could compute a triangle between the three points — viewpoint one, viewpoint two, and the aurora itself — to determine how far it really was.

The results were surprising.

Despite auroras feeling, to the casual observer, close enough to touch, Cavendish found that they were actually at least a hundred kilometers (or 60 miles) high up in the atmosphere. A decade later, Kristian Birkeland speculated that they were caused by currents flowing in the northern atmosphere — a sort of celestial neon display, so to speak.

In 1619, Galileo named the phenomenon “aurora borealis” after the Roman goddess of dawn, an etymology the Disney version of our princess shares.

Aurora (the Goddess, not the princess or the phenomenon) is known for — you guessed it! — welcoming the dawn. The rest of her story is, however, quite the opposite of the sleeping beauty. One of her lovers was Tithonus, the prince of Troy.

However, Tithonus was a mortal, meaning he would eventually grow old and die, unlike the immortal and eternally beautiful Aurora. Because of this, Aurora begged the god Jupiter to grant her lover immortality. And so Jupiter did, but Aurora had forgotten to ask for eternal youth to accompany the immortality.

While Tithonus lived forever, he continued to age, growing older and more shrivelled over time. Eventually, he became so weak he could neither move nor lift his limbs, and Aurora put him out of his misery by turning him into a cicada — in which form you can still hear him babbling endlessly on.

Today we know that auroras have their origin in outer space, and are harbingers of an amazing scientific phenomenon.

It begins in the sun, that ever-present nuclear reactor, which ejects clouds of gases from time to time. These powerfully charged clouds break through the sun’s surface, and, within a day or three, end up colliding with the Earth. This would be the end of the world as we know it, if it weren’t for a hidden protector: the Earth’s magnetic field.

Remember me mentioning that the particles were changed? Well — that charge is an electromagnetic charge, and it gets deflected by the magnets; sucked into the Earth’s magnetic field. From there, the charged particles flow along the lines of the Earth’s magnetic field and into the polar region. They release energy in Earth’s upper atmosphere, colliding with oxygen and nitrogen atoms to produce a dazzling auroral light.

Isn’t it fascinating? Iceland is your best bet to view the aurora borealis, compared to other countries, because of key factors such as low light pollution, dark nights with no clouds, and moonless nights with enough solar activity.

The story of Aurora, the Sleeping Beauty, has taken many forms over the years — and has its roots in many different cultures. The position of women in society has evolved a great deal since the first known version of the tale in 1200 CE, but what has remained common is the role that beauty plays in it.

The primarily German epic begins with a warrior maiden who is punished by the Norse god Odin for deciding against him in a dispute, imprisoned in a tower surrounded by flames. She remains asleep until she is rescued by a heroic figure who kisses her awake.

In this version, there is no happily ever after and she dies in the end — in many others, a pleasant life of marriage and children is assumed.

Even in stories where there is a happy ending, it is difficult to ignore the lack of consent in our day and age. Whether that’s with the kiss — or some of the more extreme atrocities in other tellings — it can often border on creepy. Aurora is often seen as so beautiful as to be irresistible, and these stories are a testament to the extremes people will go to in order to possess something they desire.

Auroras can be deceiving: they’d appear to be close enough that you can literally touch them but the fact is that they reside high above in the layers of the atmosphere, about 100 km above the Earth.

Though auroras are so ethereal and only visible for a few hours, people have spent lifetimes observing it, and they’ve come up with a few eye-openers.

Unlike the princess, who is radiant all day, the heavenly auroras are visible only in the dark. It is a misconception that aurora borealis can happen at any time — it can, but you won’t be able to see it any more than you can see white marks on a blank paper.

Other planets have also been gifted with auroras: since they’re caused by distortions in the magnetic field, planets with stronger magnetic fields produce even more complex and stunning auroras. This includes Saturn, and, ironically, if you’ve been following along with the Tithonus story, Jupiter.

That said, you don’t need to travel elsewhere to see a stunning display, because auroras can also be seen from orbital space — think the view from a satellite. NASA has already provided us with amazing imagery of the aurora borealis, and now that space tourism is about to be a thing, it looks like they’ll have their first attraction sorted out! Technology has driven us to a level that is bewildering.

And finally, a word of caution: don’t whistle at an aurora. If you do so, it is said that spirits of lights will come and take you away with them. Of course, some foolhardy people whistle at the auroras anyway, to call them closer, so they can whisper their messages to the dead .

As you can see, the aurora borealis is an event of both science and sheer beauty that go hand in hand. Nature has proven that the two are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Though the mechanism behind an aurora is now known in scientific detail, it is still enchanting enough for mythology to continue growing around it.

Will people stop being afraid of light-spirits first, or will a future NASA mission conduct a fun experiment to play whistling noises at an aurora from space? Given that NASA’s Curiosity Rover once played Happy Birthday To You on the surface of Mars for the first time in the history of that copyrighted song, I’d say all bets are off.

Like the fairytale of the Sleeping Beauty which manifests numerate colours, aurora borealis couldn’t be less enchanting.