Kerb Appeal

A road is made, but a route is found: here’s how the threshold’s cousin steps up the roadside game.

A road is made, but a route is found: here’s how the threshold’s cousin steps up the roadside game.

As an architect and a movie-goer, I love a good movie set; specifically, a good villain’s hideout. Think of the deserted elephant graveyard in The Lion King , the Bates Motel in Psycho, or even Miles Bron’s house in the The Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery. Villains’ houses tend to be dramatic, and ominous, and (often) more impressive than any other location in the movie.

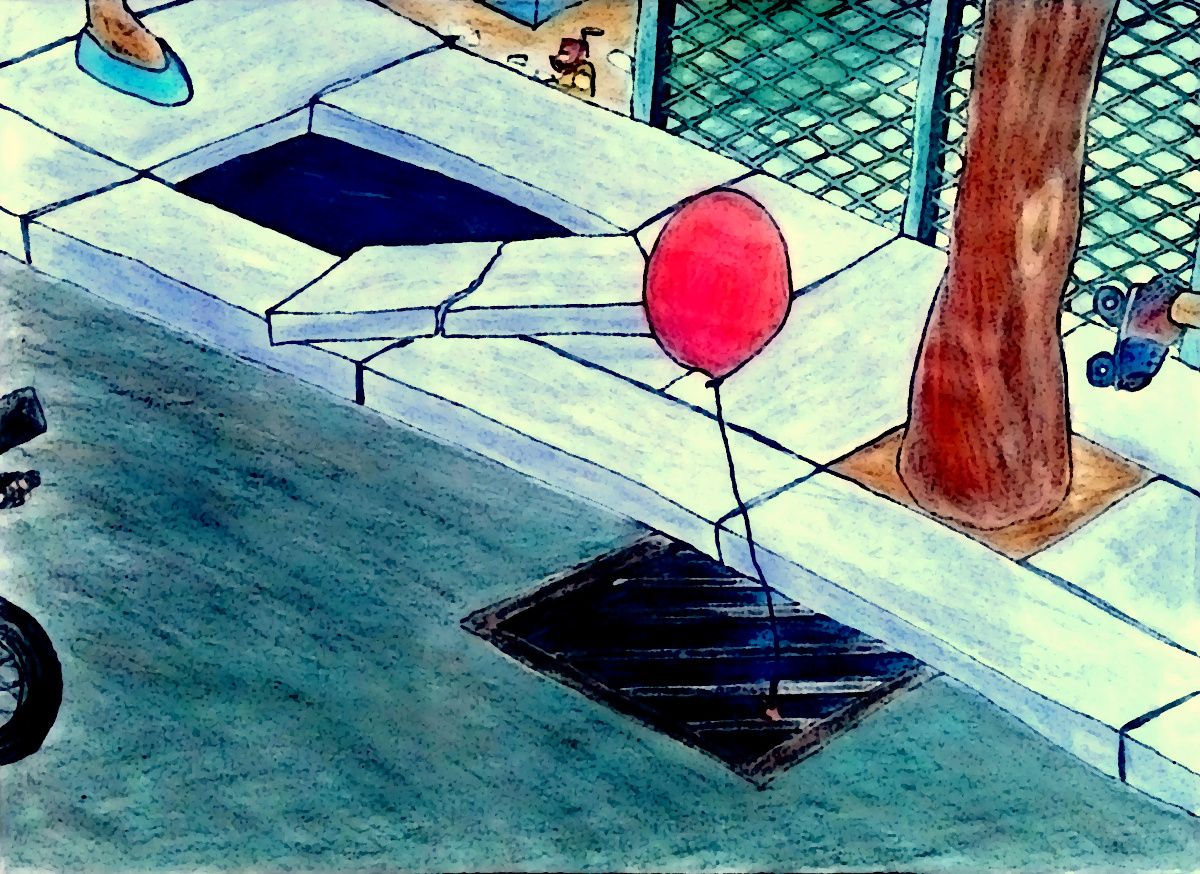

I think one of my recent favourites has to be from the movie IT, which features the under-the-kerb storm drain of Pennywise the Clown. This unconventional lair is so uncomfortable-looking, but it works because of its ubiquitous nature—there’s a kerb by the side of every pedestrian-friendly road. And this villain’s hideout shows how even the most non-showy places hide some of the most frightening evils.

In the world of Pennywise the Clown, there is more to a kerb than meets the eye. And in that, it is actually similar to real life.

Kerbs, apart from being the lair of villainous clowns, are actually useful, and evolved partially as a response to one of the biggest predators in our lives today- motor vehicles.

A kerb, Wikipedia tells us, is the edge where a raised pedestrian path meets a street or a vehicular roadway. The word ‘kerb’ (or ‘curb’ in Canada and the US) comes from the Latin curvus, meaning bent, or curved. A close cousin of thresholds, kerbs have been in use for ages (with their presence documented, atleast, in ancient Pompeii), but they rose in popularity with the rise in horse-drawn and motor vehicles in the late 18th century.

Kerbs are meant primarily to separate pedestrian and vehicular areas on a street—both physically and visually. They discourage cars from leaving the road, and ensure a safe walking space for humans and animals. The curve of the kerb also helps direct rainwater off the footpath into a storm drain; and of course, they are at the perfect height to sit down after a drunk night out.

The height of a kerb is a crucial element of its design. It is high enough to stop a car from getting on to the footpath, but low enough that an average human can easily take it in their stride. This, however, makes kerbs the antagonist in the accessibility debate.

That a kerb lets one walk on the road is admirable. But is walking the only way of getting around town?

It was around the 1950s when the idea of accessible design began to emerge. As war veterans returned to civil society, the lack of accessible spaces and usable products became more noticeable, and activists began to advocate for more user-friendly public-use design.

Kerb cuts made it possible for people in wheelchairs to walk independently on the road, but they also made it easier for others. Kids, the elderly, cyclists, and injured people found it much easier to climb up the ramps than to walk up a step. By challenging the notion of what was an accepted aspect of road design, kerb cuts actually eased the experience of walking on the road for a greater majority of users.

Today, it is the kerb—and its evolved, responsive design, with well-made kerb cuts- that decides what areas a person can go.

It is also the kerb that defines the road, not the area that has been paved.

Consider a roadway in the middle of a dry, barren field. What makes a motorist stick to driving on the driveway? In the absence of traffic, yes, any driver would drive on the well-paved road. But if the road was more populated with vehicles, a speeding driver would be more than happy to take a cut from the side to overtake those in his front.

As anybody who has lived in any Indian metropolitan city knows, it is not the presence of a road that compels people to drive along a certain way, it is the lack of a definite barrier.

On routes with heavy congestion, all vehicles play traffic tetris, looking for the most efficient way to get ahead. You can pave an elongated rectangle of an area and mandate that cars travel only on that patch. But that does not mean they will. A travelling vehicle will ideally look for the most efficient way of getting to the end of its journey.

Roads, you see, can be made. Demarcated and decreed. But the same cannot be said of the routes people actually decide to take. People—in a car, and in life—move how they find space. Not how they are allotted it. A road is made; a route is found. And so it is that our kerbs and footpaths are what stop vehicles from spilling over, keeping them from pedestrian areas. They act as a shepherd dog to the flocks of traffic that line our roads, deftly directing them a certain way.

Everything on a road is meant to be in motion, but what keeps it in order? The things that stand still. Architecture defines movement.

Edges and borders are a human invention, but they impact other lives as well. Built forms direct movements that we may not have foreseen while designing them.

Take the case of deer in the Czech Republic. The Czech Republic and Germany are separated by a lush forest, which is home to a certain species of red deer. During the Cold War, the (erstwhile) warning countries of West Germany and Czechoslovakia built an electric fence (the ‘Iron Curtain’) between the countries and through the forest, making it almost impossible for people to migrate to either side. What they did not foresee was that it was difficult for the animals to do the same too. Where once the deer could traverse freely across the land, they learnt to stay away from the fences, and kept to either the Czech or the German side of the forest.

Today, the Iron Curtain is down. The fence has fallen, and there is peace in the land. Yet, the deer stick to their sides of the forest: a behaviour learnt during the days of the war, which was then taught to forthcoming generations.

Lest you think the deer foolish, I should point out that something similar can be seen with the roads the (human) Romans built. During its heyday, the Roman empire had a vast and well-connected network of roads, stretching from modern-day Scotland right up to Iraq. And, while the empire faded away in time, the impact of the network remains to this day. The trade routes that strengthened over time, and the cities that sprung up at the nodes, came to define urban clusters as Europe marched through the ages. The roads disappeared, but architecture around it remained and prospered.

Built form thus has the power to allow or discourage (and, therefore, define) movement. This movement, repeated over time, becomes habit; habit in turn, compounded over generations, becomes cultural wisdom, built to suit a particular context.

Most of our cities and road networks grew and exist similarly. We are all just deer avoiding imaginary boundaries.

Does that mean we must listen to everything that is passed down? Of course not. The Iron Curtain deer may not be dumb, but they are certainly out of touch with the times: there is no reason to continue sticking to their side of the forest. What was an intelligent behaviour till about 25 years ago is simply not relevant anymore.

New or traditional; general or specific; any design needs to be understood for context and admired for its function. But it needs also to be assessed regularly, to see if it still makes sense for the new world. A kerb is a fantastic idea—it is needed and useful, clearly. But is it, always?

And, should it really be tall enough to conceal villainous clowns?