In the Style Of

AI is copying the work of artists. But when the artists run out, who will it copy from?

AI is copying the work of artists. But when the artists run out, who will it copy from?

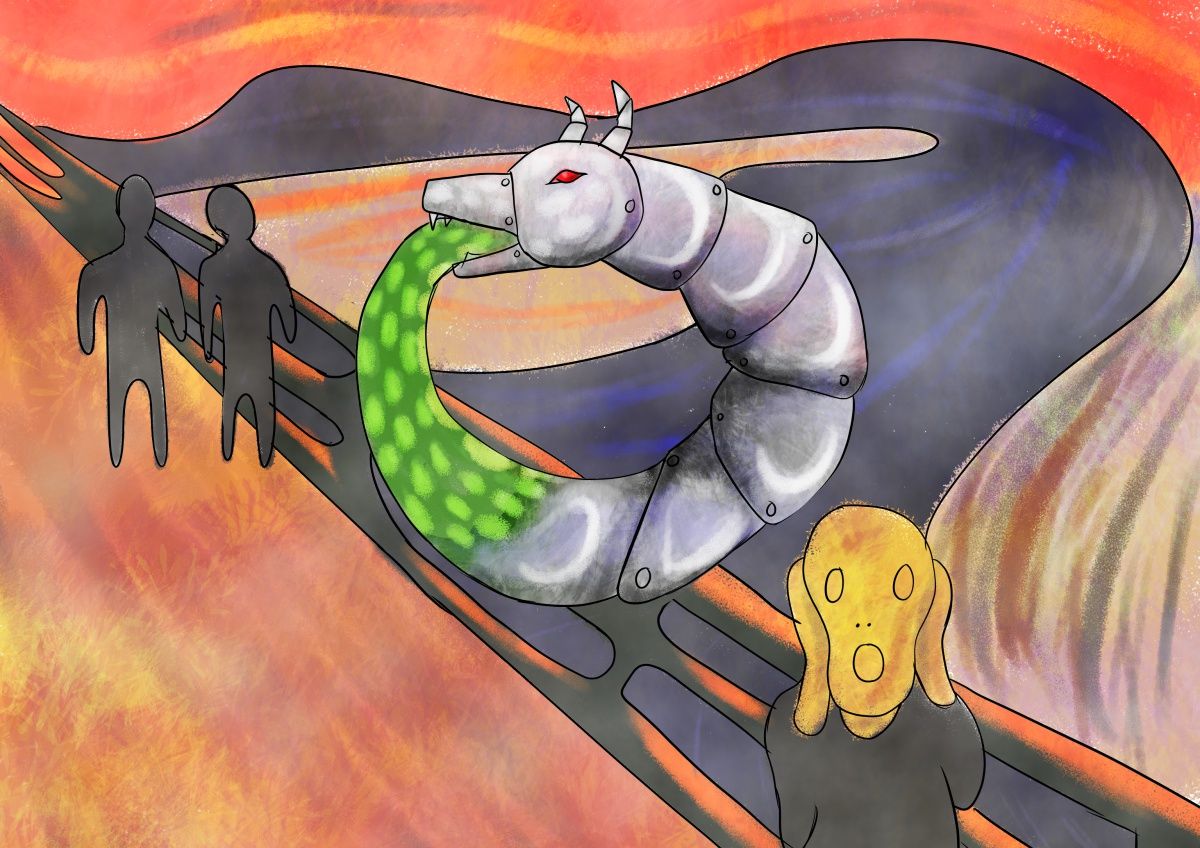

Edvard Munch’s most famous masterpiece, The Scream, is instantly recognisable. A wavy, discordant landscape coloured in—depending on which of the four versions you’re looking at—yellows, oranges, blues, and reds. In the centre is a blob of a figure—sometimes with eyes, sometimes without—hands raised to the face in tortured anguish.

And though it’s all visual, it isn’t hard to hear the scream: a sound that, depending on your thinking and interpretation, could be an expression of primal anguish and horror; the wail of madness from a psychiatric ward; the call of the human psyche; a supernatural cry from Nature itself…

…or the interference that comes when two laptops try to join the same Zoom call from the same room. This problem is an increasingly common one, and it’s what companies like Around are trying to solve.

Why does Zoom interference average to a scream? Here’s one way to think about it.

When you say, “Can you hear me?” into your laptop, that sound gets sent into the call, and out through your neighbour’s speakers…from where it falls right into your mic again, slightly blurred and broken up by the travel. Of course, this sends your “Can you hear me?” right round the circuit again, and round and round it goes, getting more distorted each time, its sounds chipped and averaged away until all that remains is a shrill streaming scream.

Actually, Zoom doesn’t discriminate between your words and background noise. All go to feed the scream. So, usually, by the time you gather the breath to ask, “Can you hear me?” you already know the answer.

With remote work on the rise, a new platform called Around came up to rethink videoconferencing. Around has innovations like circular viewports to reduce camera anxiety, but one of the main selling points is noise cancellation. The platform uses AI algorithms to figure out what’s your voice, what’s background noise…and what’s the echo of your voice coming back through your neighbour’s speakers.

With Around, you can have many people sitting next to each other on the same call, and talk freely without interference.

In the past few years, AI or Artificial Intelligence has been put to many different uses, some more spectacular than Around’s. We now have AIs that can not only detect but also create new sounds; AIs that can write essays for you based on prompts, and even AIs that can draw you “a robot, but in the style of Edvard Munch’s The Scream”.

How did people get computers to do all this? Despite its more sentient branding, most of today’s AI engines are essentially statistics on circuits.

In 2011, the National Geographic ran a feature on the world’s (then) seven billion humans. This included statistics on the age, height, distribution, and life expectancy of various people. And, just for fun, they included a profile of the “world’s most typical person”: a 28-year old Han Chinese.

Of course, averages don’t always make sense. The average number of people in a US household in 2022 was two and a half—but good luck trying to find a family with exactly that number of people! Still, the National Geographic’s “most typical person” was a fun example which combined many averages—the average age and the average nationality, among others—and, with the help of digital artists, came up with a picture of an “average face”. They also included other stats, such as: the average person has a cellphone, but not a bank account.

Today’s “AI art” is created using a similar technique, but automatic and without the help of humans. Algorithms figure out what configuration of pixels show properties like “being vivid” or “depicting a cat” or “appearing in the style of Edvard Munch”. Then, they generate pictures that have the same statistical properties.

And, it seems to work!

Today, The Scream is an integral part of popular culture. It has been imitated, parodied, duplicated, and yes, used as AI training data. The original paintings are all valued at tens of millions of dollars. Between 1983 and 1984 the pop artist Andy Warhol made silk-screen prints of several of Munch’s works in an attempt to ‘desacralise’ them: that is, to remove their “sacred” qualities and make it accessible to everyone.

Given all the fuss over one (or four) artworks, AI art can seem like a breath of fresh air. Art pieces have become status symbols and investment instruments, with people buying them not to appreciate their beauty but in order to sell them again for a higher price. With AI bringing art to everyone’s fingertips, this won’t happen any more.

Incidentally, Munch himself intended The Scream to be more widely available. Along with the two oil and two pastel versions of his work, he created a lithograph of his work to be printed in bulk. About 45 copies were printed before Munch was called away on some family business. Unfortunately, when he came back, his engraving of The Scream had been wiped away to form a “clean slate” for someone else’s art piece.

Making copies is what powers AI content creation, but making copies is also causing it trouble. In November 2022, a lawsuit was filed against Microsoft for their GitHub “Copilot” product.

GitHub is a code-sharing platform, where people can host their open source projects: that is to say, they can put up the code behind the apps and software that they write. GitHub also has a code editor, and that’s where Copilot comes in. Powered by AI algorithms, Copilot looks at what you’re typing and types out the rest of the program for you.

It’s like autosuggest, but for code.

The problem? GitHub Copilot was trained on code from all the open source projects GitHub was hosting. But “open source” doesn’t mean you can do whatever you want with them! Most open source projects at least have a condition saying you must give credit where the code is used. Some “free-software” licences go further, stating that, if you use any of the code, the project you use it in must be released under a similar free-software licence. A few projects don’t have any licence at all.

Significantly, none of the licences say it’s okay for the code to be used as training data for robots.

The Copilot case is being closely followed by writers and artists, because they are in the same boat too. Companies like Microsoft (which owns GitHub) are trawling through their hard work on the Internet, feeding it into algorithms, and creating tools that may eventually put those same artists and creators out of business.

Already, artists like Greg Rutkowski—creator of fantasy scenes for games like Dungeons & Dragons—are dropping out of search results, replaced by AI offering to draw things “in the style of Greg Rutkowski”. Artists who take years to develop their style and palette are now dismayed to find their hard work replicated a thousandfold with a single click.

If, from what you’ve heard about art sales, you’re thinking of artists as rich people who could do with a little ripping-off from, think again. After all, as widespread as the stereotype of unaffordable art is that of the struggling, penniless artist. Edvard Munch’s father was not happy about the former’s decision to become an artist—but he still had to send money for his son’s upkeep.

Today, artists are finding themselves out of a job due to competition from AI—and, to add insult to injury, that AI is often trained on the works of those very same artists. And companies aren’t being responsive. When Carolyn Henderson noticed the work of her husband Steve was being used by the AI ‘Stable Diffusion’, she tried to ask the company to have it removed. However, her request was “neither acknowledged nor answered”

Designer and programmer Matthew Butterick, one of the initiators of the Copilot lawsuit puts it in financial terms. “Even assuming nominal damages of $1 per image,” he writes, the value of this misappropriation would be roughly $5 billion.

In January, Matthew Butterick teamed up with a few other artists to plan a new lawsuit. This time, it’s intended to help artists fight for their rights as well.

If you download and use an image off the Internet, you’re probably violating international copyright law. Contrary to popular belief, the thing that gives you a copyright is not adding a ‘c’ in a circle or writing up a licence. In most countries, the very act of creating something automatically gives you copyright on that work.

The core idea of the copyright is this: to protect the rights of the artist; to make sure they have a say in where and how their work is used. They came up with the rise of the printing press, to make sure authors were compensated for their hard work, and have been around ever since. That’s why copyrights expire after a while: when the original artist is long gone, there’s no need to restrict the rest of the world from using their works.

Of course, copyrights can be taken too far. The Walt Disney Company is known for lobbying for longer copyrights, preventing works from expiring and entering the public domain. What would happen if this were taken to the extreme? That’s what sci-fi author Spider Robinson explores in his short story Melancholy Elephants.

Set in a world of long copyright periods, Melancholy Elephants begins with a new bill aimed at extending the copyright period—forever.

The problem? Art, by its very nature, involves being inspired by other works. If all the artwork is under copyright, what is left to be inspired by? But the story takes things a step further: there are a limited number of sounds a human ear can distinguish. Remove the sounds that certainly won’t be considered “pleasing music”, and what will be left? Still a large number of possibilities, the protagonist of the story says, but certainly not infinite.

If every work is entered into a copyright database, and remembered forever, we may eventually run out of new things to create. We simply won’t be able to, because it’ll all be already created, sitting in some copyright database somewhere. And that, claims the protagonist, would be disastrous for the human race.

Today’s world is in some ways the opposite of Melancholy Elephants: instead of every work being copyrighted, everything on the Internet is up for grabs.

But in some ways, it poses the same threat to today’s artists. Instead of locking down work and preventing inspiration, AI art could generate work in such volumes that there’d be nothing left to invent—everything an artist thinks of would have been already drawn by some AI or other some time ago.

A world filled with AI-generated images raises the question: is it really art? Scientist and entrepreneur Dr. Gary Marcus compares the work of AI to pastiche.

Pastiche means creating a work of literature, music, visual art, or any other form of art, really, this is designed to mimic someone else’s style—such as creating a painting in the style of Edvard Munch. And GPT-3, writes Dr. Gary Marcus about the popular text-generating AI, “is the king of pastiche”. It can make an imitation of any text if prompted properly—but what it creates will be determined by statistics, not thought and understanding.

Other people have a different view. Is AI-art really art? The answer often is: it depends.

“Art is not a skill or a club,” blogs programmer James Leonardo, “it is an act of expression.” If someone carefully guides an AI to create a specific scene they had in mind, that could be called art. On the other hand, if someone waved a hand to say “just generate some optimum graphics to go on top of my SEO content boosting piece”, the resulting image would be just that: an AI-generated image; not art.

In October 2022, stock photo company Shutterstock announced a cooperation with OpenAI, the company partly owned by Microsoft. With this new agreement, OpenAI’s image generator DALL-E would be directly integrated into the Shutterstock interface.

On the same day, though, Shutterstock also announced a Contributor Fund, that would pay money back to creators when their works were used to train AI. What’s more, Shutterstock is banning the sale of AI images that are not made using their DALL-E integration.

Some artists have welcomed the move while others are sceptical, but everyone feels that solutions such as this are the way forward. After all, the main concern of artists is that their work is being taken away from them without permission or consent. It looks like AI is here to stay, and there is no reason why it shouldn’t as long as it’s used ethically.

What’s clear is that the AI industry has to work together with the artists whose work they plan to use. Fast as AI art generators are, they, ultimately, still need artists to guide them.

To find out why, one only needs to imagine the alternative.

What would a world of AI art look like without artists? Humans on a scroll aren’t used to being picky about graphics. The sketchiest sketch and the stickyest stick-figure is passed around approvingly as long as it helps bolster the joke or political comeback it’s meant to illustrate. AI-generated images are miles ahead of this, and people would happily share it across the Internet.

Today’s Internet, full of human-created imagery, is fertile ground for training algorithms. But as artists are chased out of their jobs and become window cleaners or delivery agents, the Internet would become filled with machine-generated art…which would end up being gobbled up as training data by other AIs. Taking the cycle to its logical conclusion, new AI-inspired AI art would flood cyberspace, and become training data for still more AI…

…round and round like the “Can you hear me?” of an echoing Zoom call.

If humans are flooded with AI art, they’re unlikely to notice if that art loses bits around the edges, returning from every cycle a wee bit more mediocre.

Edvard Munch’s figures cower before our eyes: pastels on a canvas; vectors in a computation; ink in the press; pixels on a page. But only people can decide what it is, exactly, that they’re telling us