City Birds

Pigeons know how to find their way home. And, they’re pretty good at making new homes too.

Pigeons know how to find their way home. And, they’re pretty good at making new homes too.

No matter where you go — there they are. Always nearby, looking at you with big, beady eyes, wobbling their little heads, thinking their little unknown thoughts. The bigger the city you travel to, the more of them you will see. No matter if it’s cold, or if it’s hot, or even if it’s swelteringly humid. They will be there, waiting for you, watching you, ready to coo at you and violate your freshly-washed car. You will boo at them, shake your fist in their general direction or, on a good day, feed the little buggers.

Scientists call them Columbidae, but we know them simply as pigeons.

Before we talk of pigeons, let’s get one thing straight: it’s not their fault that you can find them all around the globe. They did not get to every city using their grimy wings. The ‘city’ pigeons started their existence as rock doves, living amongst the cliffs and hills of Europa, North Africa and western Asia. Their only crime was to be domesticated by us, humans, who took them with us wherever we went, and then set them free when we were done.

Unlike most unfortunate pets, pigeons didn’t die out. They adapted to city life. Tall buildings became their new high cliffs; concrete jungles their new wilderness homes.

If not the first domesticated creature ever, pigeons were definitely the first domesticated bird. Their relationship with humans can be traced as far as 4500 BCE, around the ancient civilisations of Mesopotamia.

The ancient Egyptians, the Greek, the Mongolians, and the Indians all had humble pigeons at their service — as pets, as a source of tender meat, or, most importantly, as quick and reliable messengers.

Pigeons are not only marvels of adaptability, but also a scientific wonder in and of themselves. Their ability to find a way home from as far as 1300 km away borders on magic. For thousands of years this phenomenon was pondered, but even today, with all our fancy computers, we don’t know how they do it.

For a long time, it was believed they had a compass hidden somewhere in their little brains. But it was proven later that even with magnetic disturbance — or, as matter of fact, any kind of disturbance at all — these mighty birds will still find their way home.

Some others say they navigate by stars, or by an infra-sound map. In fact, a study by Oxford University showed that pigeons can identify and navigate by landmarks, including roads and major motorways.

Or, perhaps, they are simply humble enough to ask for directions.

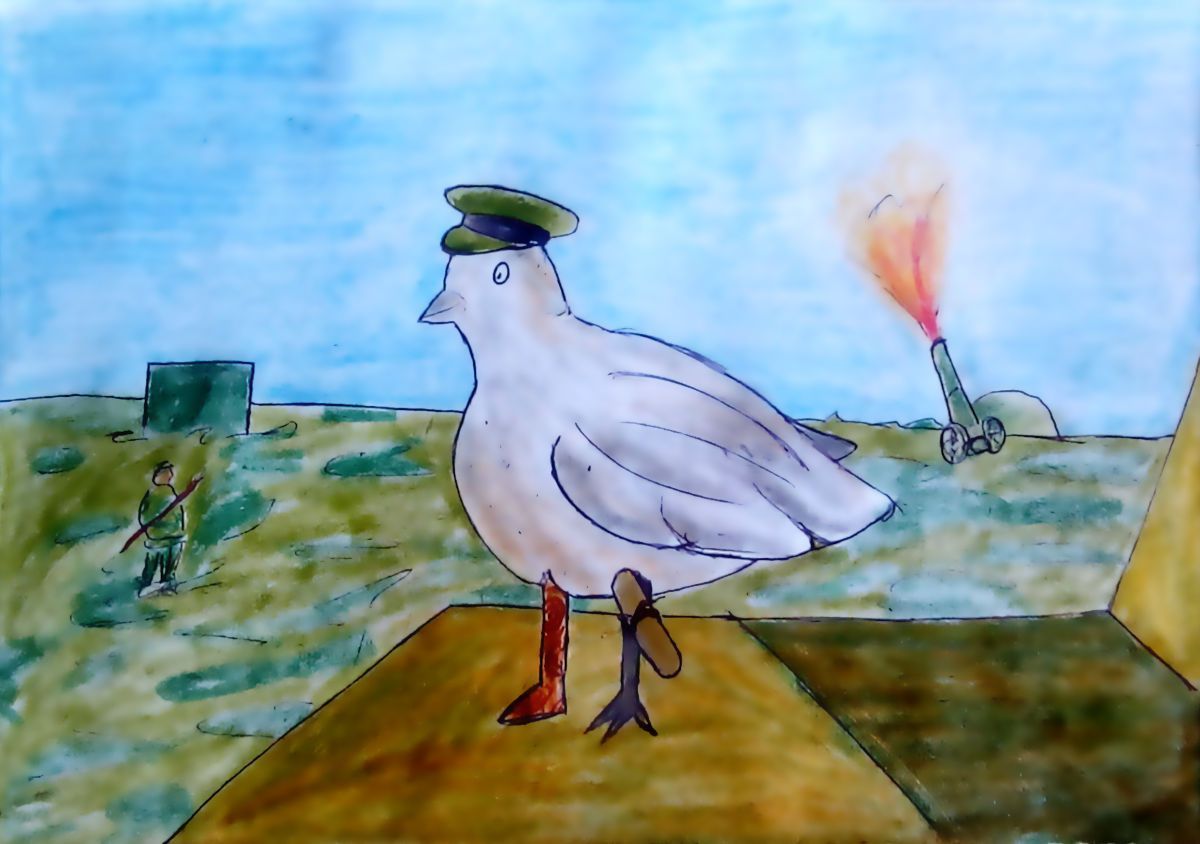

It was the beginning of October, 1918, and the First World War raged on. Major Charles White Whittlesey was trapped on the side of a hill with no food or supplies. They were well hidden, and no enemies knew where they were — unfortunately, neither did any of their allies. They would often get hit by gunfire from both sides, quite by chance but damaging nonetheless.

Major Whittlesey tried to send out runners with messages for his allies, but they kept getting intercepted or killed by the enemy. With men dying and their strength dwindling, and only two hundred of the original 550-odd men, the Major changed tack and started sending pigeons instead.

Out one pigeon went, but it was promptly shot down. The second one met the same fate. By this time, Whittlesey’s allies tried to provide a “barrage of protection” — but since they didn’t know where exactly he was, they inadvertently started firing towards Whittlesey himself.

And then, out was sent Cher Ami.

A white pigeon, braving the bullets and carrying a canister on her left leg. Inside was a note written on onion-skin paper: “We are along the road parallel to 276.4. Our own artillery is dropping a barrage directly on us. For heaven’s sake stop it.”

As Cher Ami set out, the enemy saw her rising up and opened fire. She was shot down but managed to get up and fly again. She finally reached base in 25 minutes with a bullet through the breast, blind in one eye, and a leg hanging only by the tendon. But she reached.

Army medics rushed to save the brave pigeon’s life, and she eventually recovered, complete with a wooden leg to replace her broken one.

At the end of the war, she received the French “Croix de Guerre with Palm” medal.

The pigeons’ incredible homing ability and our incredible ability to wage wars has lead to a significant use of the bird in warfare for most of human history. The ancient Greeks used them; the Persians used them; Julius Caesar used them to keep track of the vast territory of Gauls; Olga of Kiev used them to burn down villages. And when the first World War broke out, the pigeons joined the fray. Used to carry important messages across the enemy line, pigeons joined every major battle all across the theatre.

World War II saw even greater use for homing pigeons, each side employing hundreds of thousands of birds for communication and intelligence gathering. And it produced its own heroes, of the likes of G. I. Joe, who saved many lives of British troops in Italy, and pigeon Paddy, who was the first to deliver the news of the success of the D-Day invasion. In total there were 32 dedicated pigeon heroes, each receiving the Dickins Medal for their service.

In 1922, United State aircraft Carrier USS Langley was undergoing conversion in Norfolk Naval Shipyard. A pigeon house was installed on the ship, with an idea to use the pigeons as a reliable form of communication. And while Langley was stationed at the shipyard, the birds always made their way back to the vessels, but after its launch, when the pigeons were release for the first time, instead of going back to their homes, they flew back to the shipyard, and roosted amongst the tall cranes, never to return to the sea again.

If pigeons’ bravery is not impressive for you, their intelligence should be. They can differentiate all 26 letters of English alphabet and can be trained to distinguish whole words. In New Zealand it was shown that the pigeons could recognise numbers and put them in ascending order. They can recognize their own reflection in a mirror, easily passing Gordon Gallup Jr’s animal intelligence test.

If that wasn’t enough, they can even judge art.

Japanese psychologist Shigeru Watanabe taught his pigeons how to differentiate between Picasso and Monet, and they managed to do it as well as any human. Then he taught them how to identify ‘good’ and ‘bad’ art, turning them in full blown art critiques. And just recently, Levenson et al. proved that pigeons can read medical images and identify breast cancer. Not bad for some city slacker birds.

But even though pigeons are widely used as work horses, they started as loving pets and are to these days. There are clubs of pigeon breeders all over the world, and some famous and powerful people confessed their love for the birds. Queen Elizabeth II still maintains royal lofts and enters her pigeons in the Golden Jubilee One Loft Race. Mike Tyson was an avid breeder from a young age and claimed that he got in his first scuffle with a bully who tried to hurt one of his birds. Nikola Tesla, after rescuing an injured pigeon, fell in love with it, claiming that “he loved her as a man loves a woman.” Pablo Picasso named his daughter Paloma, which means pigeons in Spanish. Then there is Walt Disney with his many lofts, Charles Darwin with his fancy breeds he used to develop the hypothesis of “Theory of Domestication”, Marlon Brando, Clint Eastwood and many, many others.

Pigeons’ fast flight can not only be used to transmit old school handwritten messages but also can compete with ADSL in speed of data transfer. In 2009, an IT company in Durban pitted a pigeon with a 4GB memory stick stuck to its leg against one of the biggest internet providers in South Africa. It took the pigeon only hours and eighty minutes to deliver the information over 80 km, while wires managed to push through only 4% of required data.

So next time you see a flock of dirty birds assault a city central with their loud kooking and slimy dropping, do not shoo them away, but thank them for their service, and spare a moment to throw them a piece or two of stale bread. They may be outdated now, but one day we will need their speed and their smarts once again.

Who knows? In the future, maybe we’ll see pigeons as internet providers.