Artificial Irrelevance

A super-smart AI may not be evil. But what it could be, is even more dangerous.

A super-smart AI may not be evil. But what it could be, is even more dangerous.

This year, SpaceX made it possible to reuse rockets, by making them land on earth instead of burning up in the atmosphere. Although it didn’t always work out, it’s a big step towards lowering the costs of space-travelling.

While Elon Musk and his men at SpaceX were working this out, on a different part of the world, a social humanoid robot was just being granted citizenship. That was Sophia, a robot developed by Hong Kong-based Hanson Robotics. Sophia was granted a citizenship by the government of Saudi Arabia, in what could be seen as a publicity-stunt, but also serves as a pointer to the future: robots are getting smarter, able to talk and express “feelings” and display a sense of humour.

Reusable rockets and humorous robots are only the two most recent creations. Humans know all about genetics, and try to tweak species to make them work better. They can build skyscrapers, and split atoms, and grow plants in an apartment complex using a nutrient-filled ‘mist’.

And sitting here, I can learn about all these achievements through a small slab of silicon that sits in my pocket.

We humans, it seems, are smarter than other animals or even our ancestors. Everyone uses their intelligence for surviving, but we humans extended this to understanding the world around us. That’s what makes us special: we try to understand more than is necessary to survive.

Besides this, humans are just another animal. It’s our intelligence that makes us human.

So what if the wonderful things we create, end up gaining intelligence themselves? What if, as seems quite likely, we end up creating an ‘Artificial Intelligence’?

Artificial Intelligence? Don’t we have that already?

Actually, what we call ‘AI’ today is not quite what I’m talking about. Today’s AI is just algorithms, or combinations of algorithms, that act ‘smart’. But they are usually only good at one specific task which they’re programmed to do, like those customer-service chatbots we’ve all interacted with, or Shazam which helps me identify my songs.

True AI would be able to do any and all of those things, and more. You wouldn’t have to program it specially; it would just pick up a skill and work on it, like we humans do today. Nobody has to write a special program to teach you to speak or swim.

True AI would be able to do all the things humans can do, but better. As a 17-year-old student I don’t have a single clue about how this could be achieved, but I can see that people are working on it. I would like to do so too — but do so with the dangers kept in mind.

Artificial Intelligence is useful. As humans, we can use it to extend our abilities, just like the other tools and gadgets we’ve made so far.

One advantage of AI is, we can embed it in things more durable and adaptable than human bodies. We could send out little bots to explore space for us on their own — no need to keep phoning home on much-delayed radio links, and no need to send astronauts who need food and oxygen and protection from radiation, who miss the company of friends and family on the way.

Or it could replace employees for jobs that can’t take the risk of an employee being ill. By example factories, which only want to make profit, and hospitals, for which it’s safer to work with AI-embedded-sterile-robots instead of humans who could carry viruses or bacteria.

Artificial Intelligence is not an object. It’s an algorithm, a bunch of code and data, which you could copy-paste into any device to make it truly intelligent. It would be able to obey your instructions, without you having to guide it every step of the way.

But what if the intelligence became self-aware? What if it started listening to itself, instead of to you?

Isn’t it too early to start worrying about AI, you may ask. Machine-learning and ‘smart’ algorithms are still a new technology, so isn’t full-fledged AI still a long way off?

I don’t think so, and the reason is Moore’s Law.

Gordon E. Moore, one of the pioneers behind the chips that power your computer, also made a prediction about those chips. The number of transistors in a dense integrated circuit doubles every two years, he said. Because more transistors equals more computing power, that translates to: every two years, computers become twice as powerful as they were before.

And this series is exponential. In four years they’ll become 4 times as fast, but in eight years the number will become 16, and the number can go to 16 million in just a quarter of a century.

Moore’s Law, is at came to be called, held quite well until 2013. Then, as it became harder and harder to fit so many tiny transistors on one already tiny chip, Moore’s Law slowed down a bit. But computing power is still increasing, albeit at a slightly lower rate, doubling in three years instead of two. A slight slowdown, but not much.

And what’s Moore’s Law got to do with AI? Well, machine-learning algorithms are based on processing data, so the more computing power available, the more powerful they can get.

Today’s so-called ‘AI’ is quite limited in nature, but it’s still very powerful. Our algorithms still need to be programmed, but they can do a lot of the fine-tuning on their own.

Take self-driving cars, for instance.

Driving would be very difficult for a computer: trying to interpret camera photographs to figure out which was road and which was sidewalk and which was oncoming car. It would be very hard to design algorithms to calculate all that, let alone program it into a car and make it all work.

But with today’s machine-learning techniques you don’t have to program all that. Programmers can code in the general idea, and then leave the car to fine-tune it on its own. And every car in the network sends back its own data, pooling it together with the others so they can together improve their algorithms that much faster.

Machine-learning isn’t just for cars. We have photo-albums trying to categorise pictures, and supermarkets trying to predict purchases, and even the keyboard of my phone trying to guess exactly which word I’m going to type out next.

Each of these is a very specific task. Ask Tesla’s driving algorithm to help supervise the supermarket, and it wouldn’t know where to begin. But I’m sure a day will come when we give our algorithms the ultimate task of all: generating better algorithms.

What if the algorithm creates a better version of itself, and that one creates a better version of itself, and it goes on till it becomes as intelligent as a human — and more?

Are you an evil ant-hater?

Probably not — but consider this situation. You’re appointed head of a new hydroelectric green-energy project. When completed, this will provide light and power for half the city, taking it a big step closer to complete sustainability. There’s only one thing: once the dam is up, there’s a small colony of ants that will get submerged.

Do you stall or cancel the project just because of a few ants? Probably not: you’ve got bigger things to worry about.

This example is from cosmologist and writer Stephen Hawking’s Brief Answers to the Big Questions, and his point is: “Let’s not bring the humans in the positions of the ants.”

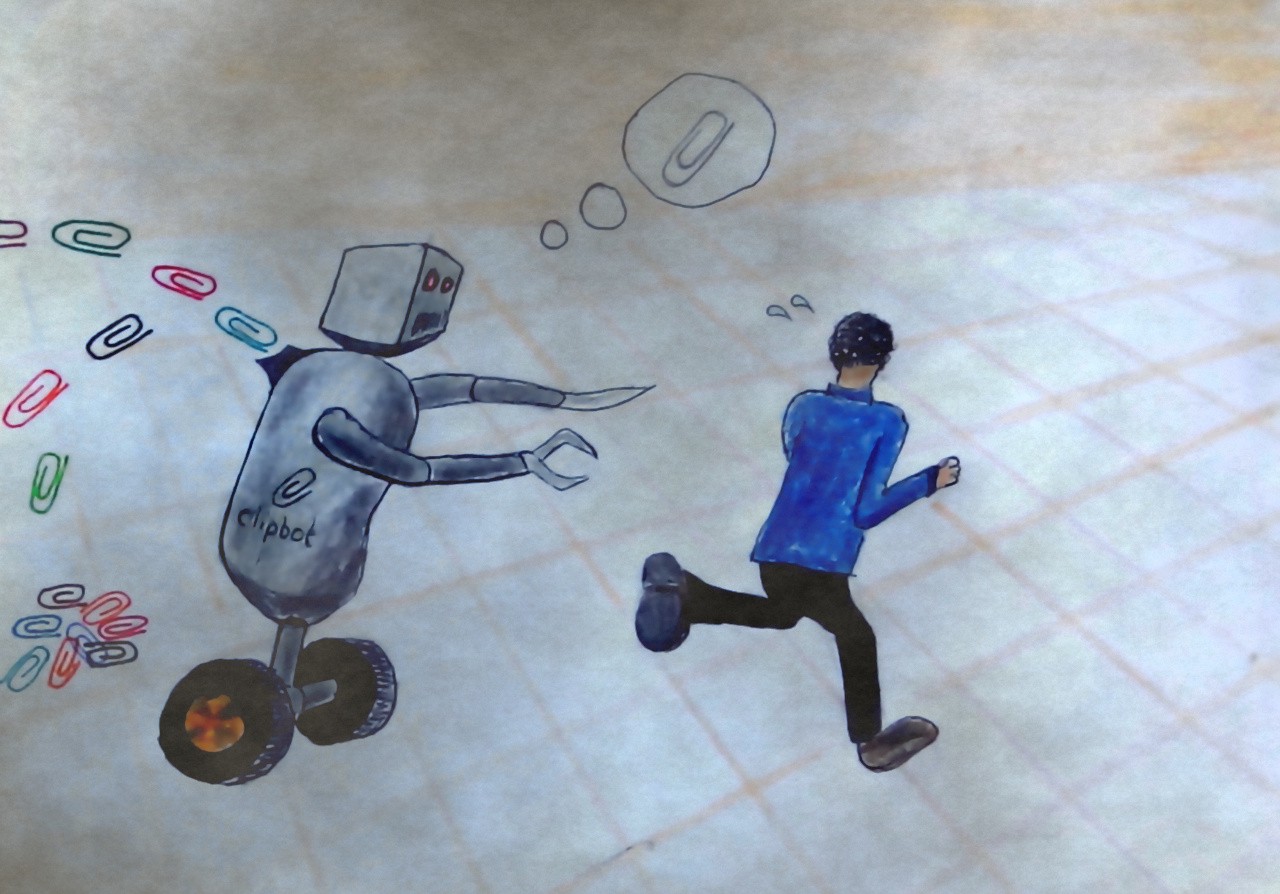

To give another example, think of the “Paperclip Maximizer”, first described by philosopher Nick Bostrom. The Paperclip Maximizer is basically a super-powerful AI, which has been give one simple task: make paperclips, and make them in the most efficient way possible.

So it sets about on its job, mining the ground for metal, then recycling the material more easily available on the surface. And when that source has run out, it proceeds to destroy houses, and ships, and bulldozers, and railway lines, and fighter-planes, and military camps, wiping out the whole planet in its never-ending quest to make increasingly efficient paperclips.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not saying AI is a bad thing, but that, as we move forward, we should be aware of the dangers and actively work to avoid them.

All the movies talk about robots going wild and AI turning evil, but I think the real danger is we simply wouldn’t matter to it, unless we had specially programmed otherwise. The AI would be so focused on gold-mining or paperclip-manufacturing or whatever, that it would run over us and destroy our homes if that was the most efficient way to go about it.

We’d be just irrelevant, like the ants.

Want to write with us? To diversify our content, we’re looking out for new authors to write at Snipette. That means you! Aspiring writers: we’ll help you shape your piece. Established writers: Click here to get started.